THE DEADLY SINS

SLOTH

by

GEOFF OLSON

______________________

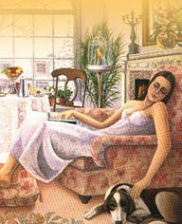

How

did sloth ever come to be considered one of the seven deadly

sins? It just doesn’t seem to measure up to the six other

offences. Yet it still retains potent force as a guilt-inducing

term. This is not as true for greed, anger and other sins. Accusing

someone of being greedy or money-obsessed is regarded as a compliment

in some quarters. As for lust, even the most baroque kink is

regarded as no more eccentric than, say, alpine yodeling or

carving driftwood. Pride is regularly confused with self-esteem.

Envy is the mainstay of the fashion industry and the advertising

world as a whole. Anger is not cool, but hey, we all have to

blow off a little steam sometimes. But sloth? Watch it. Accuse

your neighbour in the next cubicle of congress with the pooch,

and you better be ready with documented evidence. For sheer

insult, only an accusation of gluttony comes close -- “fat

pig” beats out “lazy slob,” but the distance

is closing.

How

did sloth ever come to be considered one of the seven deadly

sins? It just doesn’t seem to measure up to the six other

offences. Yet it still retains potent force as a guilt-inducing

term. This is not as true for greed, anger and other sins. Accusing

someone of being greedy or money-obsessed is regarded as a compliment

in some quarters. As for lust, even the most baroque kink is

regarded as no more eccentric than, say, alpine yodeling or

carving driftwood. Pride is regularly confused with self-esteem.

Envy is the mainstay of the fashion industry and the advertising

world as a whole. Anger is not cool, but hey, we all have to

blow off a little steam sometimes. But sloth? Watch it. Accuse

your neighbour in the next cubicle of congress with the pooch,

and you better be ready with documented evidence. For sheer

insult, only an accusation of gluttony comes close -- “fat

pig” beats out “lazy slob,” but the distance

is closing.

It

seems like most of us hardly have time for sloth. As a culture,

we’ve never been busier. Many workers are holding down

more than one job, putting in 60-plus hours of work a week.

We live in a time that celebrates high-speed action and boundless

physicality. Yet ironically, there has never been greater indolence

and isolation in the North American population, fed by television,

the Internet and video games.

By

combining sloth with that other so-called sin, gluttony, our

health has hugely declined as a population. It’s estimated

that obesity and physical inactivity costs Canada $3.1 billion

annually and leads to the death of about 21,000 Canadians a

year. Over the next decade, at least 3 million Canadians are

expected to develop Type 2 diabetes, a lifestyle disease preventable

by good nutrition and physical exercise.

Yet

sloth is more than laziness and idleness. In the original sense

meant by the early Christians, it is a surrender to despair.

Sloth annihilates the will. In this sense, the condition is

akin to clinical depression, which is characterized by a retreat

from most activities, social or otherwise. Yet few of us think

of sloth as a sin in any real sense. At most we see it as a

character flaw, and with the rise of the reporting and treatment

of clinical depression, as an illness.

A Christian

monk named John Cassian, who lived in the Egyptian desert more

than 1,000 years ago, knew the condition intimately.

“It

is a torpor, a sluggishness of the heart; consequently is closely

akin to dejection; it attacks those monks who wander from place

to place and those who live in isolation. It is the most dangerous

and the most persistent enemy of the solitaries.”

Long

before the rise of Christianity, Greeks and Romans understood

what would later be known in the Middle Ages as “melancholy.”

The Latin poet Virgil’s phrase, lacrimae rerum,

the tears of things,” describes sadness implicit in life

itself. Today John Cassian would be put on a regimen of Paxil,

Effexor, or any one of the many antidepressants that have been

prescribed to 25 percent of the US population. (As for Virgil,

he might be writing ad copy for the Pfizer account.) Never before

have we seen sloth -- in Cassian’s depressive sense --

grip the North American population as it has in the past decade,

and never before has it been more profitable to treat.

It’s

a complicated topic, to say the least. How much of the current

discontent out there is due to the pharmaceutical industry “pathologizing”

an inevitable human condition? And how much of it stems from

a heightened reaction to modernity, where every trend has a

half-life of a week, and certainty (job-wise or otherwise),

is a thing of the past? And in any case, who would begrudge

sufferers access to medication that often delivers them from

the worst aspects of this existential scourge? Yet when antidepressants

are routinely distributed by teaching staff to students in some

US high schools, we have cause to wonder how much of a mood-manipulated

society we are becoming. Aldous Huxley’s novel, Brave

New World, with everyone going to the “feelies”

high on “soma,” is looking less like fiction and

more like fact.

Sloth

appears to have been spun into a “deadly spin,”

a condition that is both reinforced and “remedied”

by hypercapitalism.

An

interesting analogy comes from animal behaviour studies, as

described in Andrew Solomon’s seminal work on depression,

The Noonday Demon. “Learned helplessness occurs

when an animal is subjected to a painful stimulus in a situation

in which neither fight nor flight is possible. The animal will

enter a docile state that greatly resembles human depression.”

In experiments on learned helplessness, changes occur in rats’

brains that resemble the neurochemical fingerprint of depression

in human brains.

How

much of today’s explosion of sloth, in the sense of a

loss of vitality and purpose, is the psychocultural manifestation

of learned helplessness?

For

a great many urban dwellers, the demanding pace of daily life

makes a certain kind of stillness - a zenlike capacity to be

peacefully in the moment - all but impossible. This stillness

is not sloth, but its psychological mirror reflection. It’s

the sense of deep peace long promised us by organized religion,

psychoanalysis, or other belief systems. Today the pharmaceutical

companies, along with the global travel industry, are the ones

to pitch this promise of peace. If we can just get out of Dodge

and into some tropical retreat, we are told in travel ads, nirvana

is ours. These ads regularly display scenes of office or rush-hour

agony, followed by shots of some far-off beach retreat with

palm trees. The camera focuses on some mid-management meatpuppet

on holiday, reclining in an Adirondack chair, with a goblet

the size of a fishbowl. Lulled by the crash of surf instead

of white noise from the office, she glories in the free two

weeks she has been working towards the other 50. Yet as the

camera pans away, we see her tapping away at her laptop.

Writes

Erik Davis, in his book Techgnosis, “The message

of those Arcadian TV spots, showing folks hanging out on tropical

beaches with their laptops and cell phones, is simple and tyrannical:

we are only free and fulfilled when we remain on the grid, on

schedule, on call.”

From

the telemarketer working two shifts, to the Hollywood North

cyberprole stuck in a chair 12 hours a day rendering fast-edit

mayhem, many of us seem to combine frantic busyness with the

physical equivalent of sloth. When some do manage to escape

the grip of work, they often find we have no energy at all to

do much more than channel-surf. They crash - and ironically,

it’s in their most inert moments with the couch commander

they are most receptive to television’s marketing machinery.

Ironically,

the pattern of increasingly sedentary lifestyles in North America

has been accompanied by less sleep. According to stats, North

Americans are sleeping one to two hours less per night than

the generation living at the turn of the 19th century. In fact,

a good night’s sleep has become something of an oddity.

At the height of the tech boom in The Wall Street Journal, an

article entitled Sleep, the New Status Symbol, detailed the

newest perk among CEOs like Amazon’s Jeff Bezos: eight

or more hours sleep. “Once derided as a wimpish failing

- the same 1980s overachievers who cried, ‘lunch is for

losers’ - also believed ‘sleep is for suckers’

- slumber now is being touted as the restorative companion.”

That

a full night of sleep can be reconfigured as a status-related

perk demonstrates just how deep the dislocations have been to

the culture over the past two decades. The sum of these changes

is undoubtedly contributing to the increasing incidence of clinical

depression.

A VISIT

FROM THE NOONDAY DEMON

“In

the middle of the journey of our life, I found myself in a dark

wood, having lost the straight path.” This is the opening

line from The Inferno, a description of Dante’s state

of mind when he came upon a hole in the world that led down

into the infernal realms. When I came across my own hole in

the world several years ago, these words had special relevance

for me. They prefaced a song by Marianne Faithful that I often

played at the time. Listening to her ravaged voice read out

Dante’s journey through the woods, I took some small but

precious solace in the capacity of art to turn pain into beauty.

My

first -- and hopefully last-- experience of clinical depression

was preceded by a mix of personal and professional disappointments.

Yet my experience, in retrospect, was all out of proportion

with what I suspect were its triggers. There were days were

I would sit for hours in a chair, staring at the floor. For

the space of a year, I fell into sloth as it was meant in its

original form as one of the “deadly sins”: a state

of complete and utter despair, devoid of joy, hope, or faith.

“The

destruction that wasteth at noonday,” a line from the

Psalms, gave the church fathers their most memorable character,

one who could strike out at the believer anytime, under the

full glare of the sun. They called the evil spirit of acedia

-- Latin for sloth -- The “Noonday Demon”.

Writes

Andrew Sullivan in his book of the same name: “The image

serves to conjure the terrible feeling of invasion that attends

the depressive’s plight. There is something brazen about

depression. Most demons -- most forms of anguish -- rely on

the cover of night; to see them clearly is to defeat them. Depression

stands in the full glare of the sun, unchallenged by recognition.

You can know the entire why and the wherefore and suffer just

as much as if you were shrouded by ignorance. There is almost

no other mental state of which the same can be said.”

In

today’s culture, the vector for depression has been reversed.

Purported negative influences from without have been internalized:

the depressive’s own brain has become the demon, and the

corrective is not a hairshirt but a prescription.

While

I was in the grip of my particular dark tea-time of the soul,

I couldn’t imagine suffering worse than mine. Yet the

many personal cases Sullivan cites in his book demonstrates

there are many rooms in the house of pain. There are catatonic

depressives who literally cannot rise from their beds, terrified

even by the thought of having to shower, who only improve through

electroconvulsive treatment. (When Sullivan’s own depressive

periods struck, he could not venture out of his apartment, and

his accompanying anxiety would fix on strange things —

even on mundane, non-threatening items on the dinner table.

“I can’t join you,” he’d say to friends

who’d call in what became his signal that he was in bad

shape, “I’m afraid of a pork chop again.”)

In

my case, I eventually went to a doctor and requested antidepressants.

The doctor prescribed Paxil, one of the class of so-called “selective

serotonin reuptake inhibitors.” I didn’t care for

the side effects, and went off the Paxil after a few weeks,

before the positive effects -- if any, for me -- could kick

in.

New

to the soul-eating experience of sloth, I eventually crawled

out of my little corner of hell on my hands and knees, without

therapy, without the aid of a drug. I may well have benefited

by turning to the medical establishment earlier, so I have no

idea how smart or dumb my latecomer’s, aborted approach

was.

I forced

myself out of sloth by socializing with friends and family.

But more specifically, I exercised, and with a rising level

of fitness, my depression slowly leached away. Self-confidence

and peace of mind returned to fill the space the Noonday Demon

had hollowed out inside me. It’s been four years since

my return to inner peace.

Obviously,

the depressive state of sloth doesn’t occur in a social

or psychological vacuum, and it’s undoubtedly more multidimensional

than just a glitch in people’s heads, a Neural-drain Demon

that strikes for some obscure biochemical reasons.

James

Hillman is a well know Jungian psychotherapist and author. In

his book We’ve Had a Hundred Years of Psychotherapy

and the World’s Getting Worse, he relates an anecdote

from a depressed patient who tells his therapist of the disturbing

sight of a bag lady in the street. He can’t shake the

idea of his mother being in the bag lady’s place. The

therapist concludes that his client has some issues involving

his mother. Hillman points out the therapist’s reading

of the situation may be only partially true, or even irrelevant,

and offers a contrary interpretation: the man may be genuinely

disturbed to live in a society that allows old women the freedom

to sleep under bridges.

The

problem is that sloth, in its original Noonday Demon sense,

has become endemic in North America -- and while there are those

whose depth of depression undoubtedly requires medical intervention,

we may be witnessing the pathologizing of a condition that has

been with us for hundreds of millennia, inextricably bound to

human consciousness. But how we live in the modern age, out

of equilibrium with the natural world and our own psyches, may

be exacerbating a collective soul-sickness.

Drug

industry ads targeting the public regularly ask a set of questions

like, “Have you ever felt sad for a whole day?”

and cite positive responses as indicative of the necessity of

a course of treatment with a mood-enhancing drug.

Even

Sullivan, who is largely sympathetic to the pharmaceutical giants,

expresses some doubts on this count. “The news that depression

is a chemical or biological problem is a public relations stunt;

we could, at least in theory, find the brain chemistry for violence

and monkey around with that if we were so inclined. The notion

that all depression is invasive illness rests either on a vast

expansion of the word illness to include all kinds of qualities

(from sleepiness to obnoxious to stupidity) or on a convenient

modern fiction.”

The

record of pharmacological treatment for the clinically depressed

has been ambiguous, to say the least. Physician-approved access

to a new range of antidepressants has literally saved some people’s

lives -- and apparently has also been responsible for children

taking their lives.

In

a pill-popping culture where no human frailty, from depression

to shyness, goes without its own ‘magical bullet’,

one has to ask: is the marketing tail wagging the cultural dog?

How long before most human suffering -- from poverty, overwork,

the collapse of community, or any number of social scourges

-- is addressed solely by expensive prescriptions, without addressing

possible cultural or psychological foundations that have nothing

to do with neurochemistry?

Sloth is being spun into another one of the Deadly Spins, with

medicine being swallowed up by marketing.

A few

years back, while attending a party for doctors in the Yukon,

I saw the lengths to which drug reps will go to cozy up to their

targets. It was like watching remoras swim alongside sharks.

In the doctor-pharma dynamic, there’s no longer a line

between the personal and the professional, shmoozing and spin,

or science and snakeoil.

In

his memoir The Noonday Demon, Solomon attends a sales

promotion for a new antidepressant, held in a “hulking

conference centre,” with more than two thousand people

in attendance:

“When

we all were seated, there rose out of the stage, like the cats

in Cats, an entire orchestra, playing “Forget

Your Troubles, C’Mon Get Happy” and then Tears for

Fears “Everybody Wants to Rule the World.” Against

this backdrop, a Wizard of Oz voice welcomed us to the launch

of a fantastic new product. Gigantic photos of the Grand Canyon

and a sylvan stream were projected onto twenty-foot screens,

and the lights went up to reveal a set built to resemble a construction

site. The orchestra began playing selections from Pink Floyd’s

The Wall. A wall of gigantic bricks slowly rose at

the back of the stage, and on it the names of competitive products

appeared. While a chorus of kick dancers wearing mining helmets

and carrying pickaxes performed athletic contortions on an electronically

controlled scaffold, a rainbow of lasers in the form of the

product logo shot from a stagecraft spaceship at the back of

the room and knocked out the other antidepressants. The dancers

kicked up their workboots and did an incongruous Irish jig as

the bricks, apparently made of stage plaster, crashed down in

thuds of dust. The head of the sales force stepped over the

ruins to crow gleefully as numbers appeared on a screen; he

enthused about future profits as though he had just won on Family

Feud.”

The

author cites himself as a case of someone saved from a ruinous

lifelong depression by the new class of antidepressants. But

with anecdotes like his, we have every reason to suspect the

sales tail is wagging the research dog. The US Food and Drug

Administration is less a bulwark these days to the pharmacartels

than their proxy. The FDA is the organ grinder, the Canadian

Health Protection Branch is its monkey, and the tune being played

is “Money.” As a result, suspect medicines rocket

through our approval system faster than a bad burrito through

a fat kid.

Your

friendly neighbourhood general practitioner no longer acts as

a firewall to the pharmacartels, not when the latter goes straight

to the people for mindshare. The principal route is through

expensive magazine and television advertisements. We’ve

all seen the television ads of laughing oldsters ambling through

bucolic settings, as the hurried voice-over rhymes off the night-of-the-living-dead

contraindications. The perfunctory legalese doesn’t seem

to put a crimp in sales -- there's still enough viewers out

there who will march off to their doctors demanding the latest

fix for the newest pathology. Not incidentally, the massive

amount of money thrown into adverstising puts broadcasters and

publishers in a less than-curious mindset when it comes to investigating

claims of health complications from designer drugs.

Sloth

is not new to the human condition, but its profitability surely

is. The question is: in a culture that moves at megahertz speeds,

how deeply will sloth’s many subterranean sources be addressed,

while the marketers of mood-enhancing solutions turn a healthy

profit? The most depressing prospect would be to discover our

highly-medicated Brave New World is the disease for which it

pretends to be the cure.

GLUTTONY,

by Geoff Olson, was published in Vol 5, No. 3, 2006.