Stephen

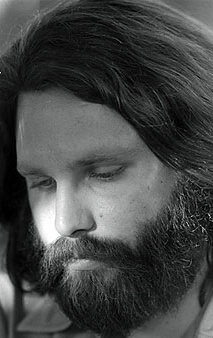

Davis’s biography Jim Morrison: Life, Death, Legend

examines the singer/poet’s descent (or ascent) into mind-altering

drugs

and alcohol as well as his promiscuity and ambiguous

-- walk on the wild side -- sexuality.

America’s

counterculture provided the background for the emergence of

The Doors in 1966: armed virgins trudging through the jungles

of Viet Nam (provoking in Morrison nightmarish visions and recurrent

dreams) and the spirit of protest that bouyed the beat movement,

the ferment of which morphed into the unique droning sound that

became synonymous with Doors music and the rise of their charismatic

lead singer who embodied, like no one else in his time, the

Dionysian principle. But as the book argues, you ignore the

laws of nature at your own peril: Jim Morrison (1943-1971) was

turned into a god by both adoring fans and media and rocketed

to dizzying heights where he lost his balance and never recovered.

Davis’

book quenches our thirst for titillation and sensationalism

by turning us into veritable peeping toms as we accompany the

Lizard through his wild antics and debauchery. And it doesn't

take long to figure out that Jim Morrison is more about

the man than the band, thus depriving us of juicy details about

by whom and how their

enduring music was created.

LIZARD

ON DEATH ROW

Being

straight and sober have rarely been a poet and visionary’s

predominant qualities, especially when under the influence of

Rimbaud and Nietzsche, which helps explain Morrison’s

love-hate relationship with death and chaos. Morisson was a

modern sacrificial lamb bearing the burden of being and the

relative insignificance of our lives. Unstable in his life and

unpredictable on stage, he sent The Doors' career spiralling

downward. His band mates, who were gifted improvisers and Coltrane

aficionados, became wary of their leader’s volatility

and with or without him would have liked to milk the cow for

as long as the records sold. But the chemistry underlying their

success was the reason why it couldn’t work that way --

a Catch 22 stuck in a melting pot of genius and torment.

Being

straight and sober have rarely been a poet and visionary’s

predominant qualities, especially when under the influence of

Rimbaud and Nietzsche, which helps explain Morrison’s

love-hate relationship with death and chaos. Morisson was a

modern sacrificial lamb bearing the burden of being and the

relative insignificance of our lives. Unstable in his life and

unpredictable on stage, he sent The Doors' career spiralling

downward. His band mates, who were gifted improvisers and Coltrane

aficionados, became wary of their leader’s volatility

and with or without him would have liked to milk the cow for

as long as the records sold. But the chemistry underlying their

success was the reason why it couldn’t work that way --

a Catch 22 stuck in a melting pot of genius and torment.

An

interesting non-correlation with today’s popular artists

put forward by the author of the book dwells on the fact that

Morrison didn’t care much for material possessions. Despite

his wealth, he never owned a house, often preferred to crash

in run down hotels or on friends’ couches, and was known

to lavish his friends and girlfriend with gifts and money. After

Strange Days (1967), their second album, Morrison grew

increasingly resentful of his stardom and the way he was perceived

by his adoring public. And while he wasn’t completely

indifferent and insensitive to the adulation, he had long grown

beyond ‘light my fire’ and yearned to be recognized

as a poet. If one concedes that his image and rock star status

were a hindrance to his goals beyond, his exceptional sensitivity

and (higher) awareness of these captive categories pushed him

farther on to the self-destructive path.

Whether

Morrison’s premature demise was brought about by a heroin

overdose as intimated by Davis, or increasing deterioration

of his body due to hard-core alcoholism and all around self-inflicted

abuse is irrelevant to the non-voyeur, for what prevails and

lingers to this day is the artist-poet who wrote constantly

and breathed poetry which he served with integrity, breaching

the fragile hymen of time and ephemeral mass adulation.

Whether

Morrison’s premature demise was brought about by a heroin

overdose as intimated by Davis, or increasing deterioration

of his body due to hard-core alcoholism and all around self-inflicted

abuse is irrelevant to the non-voyeur, for what prevails and

lingers to this day is the artist-poet who wrote constantly

and breathed poetry which he served with integrity, breaching

the fragile hymen of time and ephemeral mass adulation.