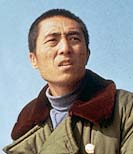

ZHANG YIMOU

interviewed by

BARBARA LONDON

This

interview is reprinted with the permission of Asia Society and

Asia Source.

Barbara London is Video and Media Curator at The Museum of Modern

Art, New York.

Zhang

Yimou is an internationally acclaimed director working in the

People’s Republic of China. His two masterpieces are Red

Sorghum (1987) and Raise the Red Lantern (1991).

He has also been highly praised for Qui Ju (1990) and

Not One Less (1999).

Zhang

Yimou is an internationally acclaimed director working in the

People’s Republic of China. His two masterpieces are Red

Sorghum (1987) and Raise the Red Lantern (1991).

He has also been highly praised for Qui Ju (1990) and

Not One Less (1999).

_______________________

BARBARA

LONDON: What interests you about making period pieces?

ZHANG

YIMOU: Most of my films are historical in nature. Since the

very first film I made, Red Sorghum, I have really

liked historical stories. But for that film, the main reason

we decided on that time period was because China had very strict

censorship. When you make a film, especially about a tragic

story, you'll have to put the characters under a certain pressure

from society, and then show how the characters fight their fate

and tragedy. But what kind of pressure are you going to put

them under? Obviously, there would be a problem doing this in

a contemporary Chinese setting: there could be censorship problems.

Seeing that everyone knew about the Three Big Mountains

on the back of the poor, we decided to situate the story in

China under feudalism. This way the subject becomes easier to

deal with in the film. Our original idea wasn't really to make

a political statement, but rather the story requires strong

pressure so that we can describe the fate of the characters.

All stories need such a background.

Today,

it is not uncommon for Chinese directors to resort to this method

when they have a story to tell. They simply trace the time backwards

and place the story in a safe time period, and not necessarily

because they are attracted to that particular time period. That

was what happened to me at the beginning of my career and I

made some historical films. After some time, you just get used

to it, and now I actually find historical stories and their

settings more interesting because they provide a larger space

for the imagination.

BARBARA

LONDON: Puccini's opera, Turandot, is set during legendary

times in Beijing. How did you get involved in the film project?

How do you feel about the three riddles in the story?

ZHANG

YIMOU: It is really a very Eastern concept to use these riddles

even though the answers to these riddles are very Western. I

didn’t spend any time solving riddles with answers such

as ‘freedom’ and ‘blood.’ This was Puccini's

imaginary Eastern story.

It

was quite interesting how I undertook to film this opera. The

Florence Opera house had been trying to contact me for nearly

a year, and had sent me many faxes asking me whether I'd be

interested in directing an opera. I was busy making films, and

didn't pay them much attention. I thought they must have been

joking. Why would I, a film director, direct an opera?

One

day, I told Zhao Jiping, a music composer, this funny story

about these people wanting me to direct an opera. He asked me

what kind of opera and I said I really didn't know, but perhaps

it was about a princess. He was excited and said that it might

be Turandot, a very famous opera with the story was

set in China. So he provided me with a videotape of it, the

version released by the New York Metropolitan Opera, directed

by an American. It was very good. After I saw it, I thought

this would be a grand opera with grand scenes, but I still didn't

understand what was being sung. The next day Zhao Jiping gave

me a rough summary of the story, and encouraged me to direct

it even if it meant that I had to give up a film. Seeing that

he was so enthusiastic, I faxed the Florence Opera house and

told them that I would consider directing it, and would like

to discuss it with them. This set the ball rolling, which resulted

in the current version of Turandot.

After

the decision was made, I decided I had to expand my knowledge

about this opera. Florence Opera house sent me a bunch of information

about Turandot, and I checked out lots of books from

a library about operas and the life of Puccini, etc. But I found

that the more I read, the more confused I got. It is really

a different genre. But then it occurred to me the reason why

Florence Opera House wanted me to direct the opera was that

they value my view as an outsider. If I studied too much about

it, my views might not interest them any longer. So I stopped

studying it and left it half-cooked. Obviously, they were hoping

that I would have some really fresh ideas as an outsider.

So

I thought about it a lot. It was set in China. I had a starting

point, and began to view it as if it were a Peking opera, with

the characters set in traditional settings and classified into

traditional roles. Looking back now, it was quite successful,

and it was really a big hit in Beijing when it was staged. It

was very well received by all my Western friends as well. I

said that I treated it as a Peking opera piece, but I really

did something that I am good at doing, that is, making it highly

visual. There's lots of slow singing in an opera, and if for

a long time nothing happens on the stage, the audience will

fall asleep. That set me thinking about visualizing it, and

in addition, making the visual effects continuous and unbroken,

so as to create continuous excitement

BARBARA

LONDON: Are there any parallels with your film Hero?

ZHANG

YIMOU: There's no direct relationship. If they are related in

any way, because they are both my productions, they are both

bold in color, with emphasis on visual effects. In fact, Hero,

as a martial art film, conveys my idea for this genre. Personally,

I think China's martial art films are different from the Western

action films. The most important difference is that China's

martial art films place a lot of importance on aesthetics, even

poetry, romance, and the beauty of the whole story. Ever since

I was little, I have been watching martial art competitions,

and have been influenced by aesthetic concepts. So when I make

martial art films, I try to differentiate them from the West's

action films, with lots of emphasis on visual aesthetics.

BARBARA

LONDON: What is special to you about the Qin Dynasty?

ZHANG

YIMOU: I wanted to make a film about the color black since I

had read in some historical material that the Qin Dynasty revered

the color black. Black was the state color. As a cinematographer,

I know that the color black is the most difficult to film. Solid

pitch black is not hard to film but what's hard to do is layered

blackness. There had been some Chinese films about the Qin Dynasty,

including The Emperor and the Assassin, directed by

Chen Kaige, with whom I had a discussion about filming black.

But none of those films did a satisfactory job in doing black.

I really just started thinking about doing black, from a visual

point of view. I thought it would be good to set the story in

the Qin Dynasty. Of course, I am from Shaanxi province, and

my ancestors were from Lingtong. Qin was my home, and I am proud

to be associated with it.

So

I decided to do the film during the Qin Dynasty and to make

the story center on the first emperor. What I didn't expect

was that this film would cause a lot of trouble. Everyone in

China knew about the massive political debate about Hero.

One article was correct in saying that it was all the first

emperor's fault. In fact, choosing a certain dynasty is sometimes

just a random technical detail. There is really no rule that

I follow. However, I have a certain affection for the Qin and

Han Dynasties, just as numerous poets have said, ‘Qin's

Moon’ and ‘Han's Gateways,’ and ‘Qin's

Bricks and Han's Tiles.’ I personally think the art of

the Qin and Han Dynasties had a certain grandiosity to them,

and a certain primitiveness, and simplicity. For instance, in

one poem, Li Bai wrote in "O' to the Hero", "Killing

one person each ten feet, no trace left for thousands of miles;

Now that the Buddha had gone, and God and enlightenment is hidden

in depth." He vividly depicted the images of the heroes.

I believed he wrote about what happened in the Qin and Han period.

Li Bai himself lived in the Tang Dynasty, so it is not likely

he'd write about his contemporaries. He'd only write about things

and people of past times. One can still see the heritage of

the Qin and Han times in my home province, and I really like

this style. Setting the film in this period gives a starting

point to fully depict the grandiosity of the bronze time.

BARBARA

LONDON: Can you talk about the score?

ZHANG

YIMOU: I have known Tan Dun for over 20 years. We are old friends

dating back to before he came to the US. He was outstanding

in his generation, the so-called ‘fifth generation’

of the Music Academy. I know all of them. He is the one who

is always coming up with new ideas. Some people who dislike

his music accuse him of being too avant-garde. I personally

think he is not constrained by traditions and is always seeking

to inject new elements in music. I really like his creativity

and his bravery. Sometimes I find his work strange. For instance,

he'd ruffle paper for hours on stage, or play with water, but

I really like him.

I heard

his score for Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon, when I

was invited to the screening in Beijing. I found the score wonderful

and it really helped the film a great deal. It was very interesting

and very thought provoking. I suddenly realized that I had lost

touch with Tan Dun for years. He really had changed a lot. I

found his music incredible, and I had a feeling that it was

going to win some awards, including the Oscar. And that was

what happened later. He really made us Chinese proud. So when

I made my first martial arts film, Hero, the first

person that came to my mind was Tan Dun. Firstly, he was a good

friend; secondly, he had that good vibe, and I hoped to benefit

from it.

Tan

Dun was glad to work with me and agreed immediately in spite

of his busy schedule. He has always had great ideas. He had

invited Perlman to play violin, explaining to me that he is

considered the world's number one violinist. So I went to New

York for the recording, When Perlman, who is handicapped, entered

the recording studio, violin in hand, Tan Dun nudged me and

whispered, "See that violin? Two and half million US dollar!"

So I was looking forward to the wonderful music produced with

such an expensive violin. Then Tan Dun brought out his own violin,

and asked me "How much do you think mine would cost? Forty

yuan! I bought it in Guizhou before I came to the US."

He insisted that the master Perlman use his forty-yuan violin

which he deliberately untuned. For over an hour Mr. Perlman

just couldn't get it right. Tan Dun said that Mr. Perlman is

known in the music world for the accuracy of his tuning. In

the end, we really did record the music played from that violin

for Hero, and it had a battered and sad feel to it.

Mr. Perlman really didn't know what to do about it. But the

next day when he came back to the studio, he was very excited.

He said each time he'd play the recording to his children, or

perhaps grandchildren, if the kids like it, it would be good.

This time his grand daughter loved it and said he'd never played

anything that wonderful. He was really excited. From this detail,

we get insights into Tan Dun's creativity. The soundtrack of

Hero is very melodious, and everyone likes the solo

violin part. It was what was played with the five dollar violin.

What he made me realize was that value is not always measured

by money. Creativity and imagination are what counts.

BARBARA

LONDON: Are you going to continue to collaborate with Tan Dun?

ZHANG

YIMOU: In fact, I was discussing our future plans with Tan Dun.

In cooperation with the New York Metropolitan Opera, Tan Dun

will compose a opera, with the story set in the Qin Dynasty.

Domingo will be The First Emperor, and it will be played in

the Metropolitan Opera. I will be the director. We are planning

to premier it in December of 2006. It will probably be played

in Los Angeles, China and other parts of the world in 2007.

The plan's already been made and Tan Dun is writing it right

now. So I will be back to New York to meet with everyone. The

Metropolitan Opera still wants me to do the homework on opera

by watching lots and lots of them.

BARBARA

LONDON: What are your favorite American movies? What do you

think of Asian Americans in Hollywood?

ZHANG

YIMOU: There are many genres of American films and I spend most

of my film time watching American films because American films

take up a large part of the world film market. There are many

American directors and actors that I like a lot. But of course,

there are good ones, and not so good ones. I am not against

Hollywood commercial films, and I watch them very often and

often find good ones there. One can't really make a generalization

about Hollywood. I am not like the French and the Italians who

are hostile to Hollywood, calling it all junk. I have varied

taste, and watch a lot, whatever catches my attention. The most

recent one that I saw was set in Hong Kong. It is a sci-fi,

ghost kind of film, mixing ghosts, vampires, etc., all together.

I don't really remember the name of the film because it was

translated in Hong Kong. But I really liked the computer animations

and special effects.

There

are many foreign directors who are seeking to develop in Hollywood.

It is true that for many directors, once they make their names

known in their own country, they are immediately bought over

by Hollywood, or rather, they are drafted to Hollywood. I think

these are all the personal choices of the directors themselves.

The large market that Hollywood could provide constitutes a

great temptation to many directors. An audience of 20,000 is

very different from an audience of 2 million. It's natural that

many directors want to develop in Hollywood so they'll have

a larger space and a larger audience.

There

are examples of Asian American directors, such as Ang Lee and

John Woo, both very successful. I think they made the right

choice in coming to Hollywood. I have often been asked whether

I wanted to come to Hollywood myself. My answer is that I am

not suitable for Hollywood. First I don't know the language.

Second, the films I make are all based in China. If I came here,

I wouldn’t be able to make the film here, not even a third-rate

film. So I know myself, and know that I can't really be separated

from the land I grew up in. I can only stay in China.

BARBARA

LONDON: Hero is not a major contender for the Oscars

given its late release in the US. How do you feel about it being

marketed as a Quentin Tarantino film, not a Zhang Yimou?

ZHANG

YIMOU: This film's release had been delayed a long time in the

US. I think this is Miramax's own plan, and I can't really intervene.

My manager also told me that the contract says the timing for

the release is also set by them. We could only worry. Jet Li

told me that at least $20 million dollars were lost as a result

of the delayed release. He did a calculation, saying that all

the Chinese people in the US had all seen it on DVDs, or VCDs,

so they won't go to theaters. But timing is still their commercial

choice, and I can't really do anything.

Miramax

asked me before whether it would be okay for them to market

it as "Quentin Tarantino presents." Quentin and I

are friends, and when he was making Kill Bill in Beijing,

I went to see him. I found out that his staff is mostly the

staff of Hero, and I joked with him that he is using

my people and we are really one family. I think this is really

an American marketing scheme, but I don't have any problem with

it. Quentin is anotherdirector who I really like. It is only

natural that they use the American way for marketing, for each

region has its own way of marketing.

BARBARA

LONDON: There are many good sources of Chinese literature to

draw from for your films. Now 10 years after you began your

career, are they still inspiring you even when China is now

more commercial?

ZHANG

YIMOU: I still think so. China has many good stories, and it

still is an inexhaustible source for our creation. And it is

not limited to literature. I have many plans for making films.

For instance, I want to make a film with the Cultural Revolution

as the background because that was an important part of my life

-- when I was between 16 and 26. It's not that I want to make

a political film, but rather show the fate of people, the love

and hate, the happiness and sadness – human nature. I

am attracted to stories that reveal the way people lived. But

unfortunately in China, these stories are still taboo. But what

I can do is reflect on my experiences for future projects. Once

I begin to make such films, stories from those ten years could

keep me busy for the rest of my life.

BARBARA

LONDON: How do you think Hollywood has influenced the film industry

in China?

ZHANG

YIMOU: I think it would be good for our marketing system to

compete with Hollywood but is it really difficult to do. Not

only Asian films, but the entire world wants to compete with

Hollywood. When you go around the world and talk with film workers,

that is always a topic that comes up -- how to fight the invasion

of Hollywood's commercial films and to protect their national

films. Both artists and governments are talking about the same

thing. Hollywood will not easily give up the market it dominates.

Hollywood is very business smart and has gotten all the good

directors from all over the world. It has got some of the best

directors in China, including martial arts instructors from

Hong Kong. So much so that we can't even find qualified people

because Hollywood is paying them more money. Hollywood attracts

talent from all over the world and handsomely rewards them.

No one can fight them simply by establishing a commission or

pooling resources and money.

A more

serious problem is that Hollywood has cultivated its own new

generation of audiences for its commercial films. In China,

young people only like Hollywood hits. They can easily name

all the Hollywood stars. American young people say, "who

of you can name Chinese stars?" No one can do it. How many

Chinese films do you see every year in the American market?

There are just a handful. We can see from here that Hollywood

really has a young generation of followers. We feel that our

national film industry is placed under pressure because we know

that the most important audiences for films are young people.

This really presents us with a challenge and we have always

taken it to be our responsibility to make good Chinese films

and do our part to influence the Chinese audience. For instance,

we show them Hero, whether they like it or not, and we present

to them a Chinese color, Chinese cast, and Chinese people.