|

|

NIGHTFLIGHT

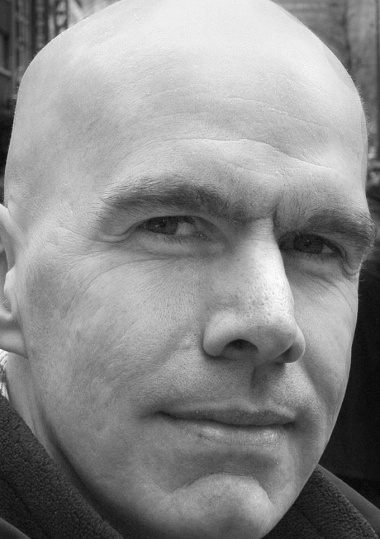

by LIAM DURCAN

Liam Durcan

was

born and raised in Winnipeg and now makes his home in Montreal

where he works as a neurologist. His fiction has been published

in The Fiddlehead, Zoetrope, The Antigonish Review,

and Maisonneuve. He won the 2004 QWF/CBC Quebec Short

Story Competition, has been nominated for the Journey Prize,

and was featured in Coming Attractions ‘03.

Nightflight appears in Durcan's A Short Journey by Car,

published by Véhicule

Press (2004).

Liam Durcan

was

born and raised in Winnipeg and now makes his home in Montreal

where he works as a neurologist. His fiction has been published

in The Fiddlehead, Zoetrope, The Antigonish Review,

and Maisonneuve. He won the 2004 QWF/CBC Quebec Short

Story Competition, has been nominated for the Journey Prize,

and was featured in Coming Attractions ‘03.

Nightflight appears in Durcan's A Short Journey by Car,

published by Véhicule

Press (2004).

________________________

Raymond

knew something was wrong when the taxi driver asked him if they

were getting close. He had been roused from a light, semi-drunken

stupor to hear the words trailing off and he paused to think for

a moment, as though some sober authority inside him was verifying

what the driver had said.

Raymond tried to speak but started coughing instead and needed

to sit forward. “The Bellcroft. I said the Bellcroft Inn.”

He looked out the side window into the rippling darkness of Vermont

countryside.

“I told you I didn’t know where it was,” the

driver replied, his eyes meeting Raymond’s for an instant

in the rear-view mirror. His head jerked nervously, as though

he were trying to make his point face-to-face with Raymond.

“You took me as a fare,” Raymond said, sitting up

on the edge of the seat and trying to peer through the darkness.

It made him feel ridiculous. “How long have we been driving?”

“About forty-five minutes. You were going to tell me when

we got close.”

“Oh, Christ. Stop the car.”

The driver’s head toggled in position as though he had heard

the command but the car continued at an unchanged rate down the

road. Raymond’s anger and confusion gave way to fear. The

command to stop was as harsh a denunciation as a taxi driver could

ever hear and now the man’s twitches seemed not pitiable

but ominous. Raymond couldn’t even remember seeing an illuminated

sign on the car’s roof, he had just got into the next car

in line once the reception was over. In the back seat, an expanse

of vinyl as wide as a park bench made him feel small and easily

ignored, and he was not particularly relieved to finally hear

the indicator’s tocking as the muted green light pulsed

in the darkness of the dashboard. No one was on the roads at this

time of night, he thought, and the act of signaling had an odd

deliberateness to it, something pathologically calm, and it froze

him. He began to panic profusely, imagining a frenzied chase through

the whiteness of the headlights followed by this lunatic, feeling

the underbrush tear him as his lifeless body was dumped into a

ditch. Vermont could be deadly.

“Stop the car,” he said again, calmly, as though

talking someone back from a ledge.

The driver pulled the car off to the side of the road. He sat

motionless with both hands on the wheel, the correct ten and

two positioning. Raymond cleared his throat, unsure what came

next now that the vehicle had stopped and the threat of volatility

seemed passed, or at least less imminent. The indicator counted

a heartbeat half of his own. The driver put his head to the

wheel and for a moment more Raymond thought about his options,

of just opening the door and leaving, of becoming that type

of person who simply leaves cabs. There were, however, subsidiary

issues: night-time navigation in rural Vermont, hindered by

an extra vodka-rocks and complete spatial disorientation, the

embarrassment of the thought of death by exposure, the hundred

graceless exits of an autumn night in the back-country. The

door remained unopened however, as Raymond found himself leaning

forward to touch the driver’s shoulder. The man was weeping.

“Look, it’s no big deal, we’ll come to a crossroads

and then we’ll have our bearings. Besides, I think the

Bellcroft is on the road to Hyde Park.” The man was unconsoled.

“It’s not that.”

Well then, Raymond thought, taken aback at the curtness of the

driver’s correction, what the hell is it? Is this therapy,

then? Some sort of work-release program for aspiring taxi drivers?

“Look, bud…”

“Allen.”

“Allen. Get to your dispatcher and just ask him for directions.”

The years of living on the Upper East side—and the inherent,

constant exposure to taxi-driver personality disorder—was

paying off for Raymond, easing him into survivalist mode like

it was a default setting.

“I don’t have a radio. This is a private car. I

just do this part-time.” He pinched his nose with a tissue

that he peeled off a larger wad. He honked and wiped.

“Do you know the area?” Raymond asked.

“No. I’m from Rutland.”

Raymond sank back into the seat. He was exhausted. His muscles

ached mysteriously, as though effort had been extracted without

his consent. The night had not gone well; Lorraine had left

for their bed and breakfast hours ago. God only knew if she

got home. And the celebration of his parents’ anniversary,

with the ostentatious expanse of the tent and the jazz band,

only worsened his mood. He felt alone at the party, and once

Lorraine left he found himself looking at his parents as they

sat at the head table until they seemed to him like imposters,

wearing familiar masks, incorporating mannerisms flawlessly,

but somehow not his mother or father. After his parents moved

to Vermont and restored their Federalist cottage, they seemed

to change, appropriating lives from architecture magazines and

home gardening shows, seamlessly indoctrinating themselves into

a genteel cult life of fresh air and artificially distressed

chairs. His father took to wearing plaid shirts and stopped

registering, or at least expressing, contempt for those around

him. His mother seemed happier too, developing an almost Buddhist

calm as she considered every angle of their tiny new box house,

a fraction of the size of the one they vacated in Westchester.

They were happy now, after years of recriminations and a trial

separation when Raymond was a sophomore at Cornell. They stayed

together, and it seemed as though the years of difficulties

and conflicts had polished them into, if not identical, then

complimentary, placid partners. And yet their newfound happiness

seemed so false that Raymond had difficulty visiting them, which

was just as well as the restored house could barely contain

the happy couple and led them to concoct the idea of the tent

for their thirty-fifth anniversary celebration. He hated tents:

the probationary atmosphere, the marquee tawdriness, and tonight

he chafed at the canvas swaddling him like a shroud. The gaiety

was oppressive, with relatives wagging flutes of Veuve-Cliquot

and talking of summer places with restricted access. The tent

had been full of family: cousins, aunts and uncles, all variations

on a genetic theme. He could detect among many in the crowd

the common features of eyes a touch too close and the prognathic

Irvine profile, among the other traits of overdrinking and morbid

self-reflection. He was only too happy to have his older sister

Didi give the toast; by that time Lorraine was long gone and

he had committed himself to a more advanced regimen of vodka

tasting. His frequent trips to the bar, along with the night

air, imparted a roguish vigour on him. Didi told him he was

stinking and asked him where the hell Lorraine was. Maybe his

legs hurt from all that walking to the bar. He remembered the

relief at seeing some unfamiliar faces and smiled at some of

the young women gathered at tables near the periphery of the

tent. Outside one of the portable toilets he side-stepped his

cousin Michael, who had been busy all evening announcing the

windfall he made investing in a technology company whose product

or function no one, including the investor himself, seemed able

to explain. Back inside, the band had started another set. People

danced through the amber light of the tent.

“I’ve been to Rutland.” Raymond said to Allen,

almost reflexively.

“Oh yeah? You ski?”

“No. It was on business.”

On a clear October afternoon, the landing gear of a small plane

had clipped the very tops of a cedar grove that lined the Rutland

Municipal airport. The pilot brought it in too low, that much

could be surmised from the height of the clipped trees and where

the plane eventually hit. It was one of Raymond’s first

assignments and because of this he was given the grunt-work

assignment of doing the measurements. He stood out in the rain,

tape measure in his hand, and put the distance at three hundred

and forty-six feet five inches. The pilot—Caucasian male,

thirty-five, good health, toxic screen negative—had less

than fifty hours of solo experience. The conditions that saw

the single-engine plane try to recover before ceding into a

bank, then a roll, and then into the ground, were ideal. As

far as Raymond could recollect they signed out the case as pilot

error.

“Who do you work for?” Allen asked, gaining composure.

“National Transportation Safety Board.”

“Is that Civil Service?”

“Yeah. I suppose.”

The admission made Raymond uneasy. People still had certain

preconceptions about civil service jobs. When he was more specific

and told people he was a crash investigator, they would simply

nod, thinking that he was the man they saw on the news, holding

up the battered flight and voice-data recorder for the television

cameras, that all that was necessary in an investigation was

to open the black boxes and listen to the final minutes of something

gone terribly wrong. He usually didn’t take the time to

explain that he was a small craft specialist, and that the light

planes flying into the smaller airports had no black boxes or

tower surveillance so that any crash was essentially an examination

of evidence at the crash scene. He and his team, two other investigators

and technical backup at the NTSB regional laboratories, would

be dispatched to the site where they would collect information

about the weather conditions surrounding the crash and the pilot

variables. Next, they would examine the plane, essentially performing

an autopsy on the craft, removing the gauges and display lights

and dissecting the mechanics.

At one time he had been determined to become an aviator. When

he first started flying lessons he thought about the different

careers and found the solitary life of a bush pilot the most

appealing to him. He pictured himself night-flying float planes

through the wilderness of northern Quebec, with the glow of

the avionics equipment and hum of the engines as his companion.

He read St. Exupéry and studied the maps that showed

the early mail delivery routes that stretched from Paris to

Dakar and then across the ocean to Patagonia. Even phonetically,

‘aviator’ had something that ‘pilot’

lacked. You could pilot a shopping cart around the aisles of

a super-market. A dinghy could be piloted.

Things were different now, though, and by the time he had his

pilot’s license, the only jobs left to consider were in

the shadowy corporate world of the small air carriers. Since

deregulation in the early eighties, small transport companies

had multiplied and made obsolete the single plane operations

so that Raymond’s dream disappeared as suddenly as St.

Exupéry over the Mediterranean. He had no interest in

hauling for the smaller carriers who he could see were cutting

costs to preserve a margin, because he knew what the cost would

come to. The move to the NTSB was natural once the planes began

to disassemble in midair for lack of anyone paid to see to their

maintenance. The work fascinated him in a way that made it seem

almost perverse to sift through failure to find a cause for

something that every pilot feared, something quite possibly

beyond their control. There were other satisfactions—more

than would be expected from simply closing the book on an accident,

or drawing attention to insufficient industry standards—and

it was something that his parents or Lorraine or Didi could

never fully appreciate. He had difficulty explaining to people

how the job changed him, how it allowed him to see that every

disaster had a starting point and a trajectory, that there was

a series of events that led to a moment of irreversibility and

complete failure. A rivet loosened, a flange flapped, and a

complex machine began to unzip itself, by degrees becoming what

it was, assuming its native state and a condition of lower energy,

returning to the ground.

The engine idled and Allen appeared to be searching for something.

He was a big man, judging from the size of his shoulders and

his posture in the driver’s seat. Raymond patted his jacket,

thinking that he had his cell phone in a pocket but nothing

was there.

“Where do you think we are?” Raymond asked.

“No idea.”

“Should we just keep going? We might find a phone booth.”

“Yeah, yeah,” Allen said, turning off the indicator

and putting the car into gear.

The road passed under them like the back of a great animal,

writhing in and out of the headlights. The stars were visible

from the passenger window and Raymond thought he recognized

a constellation as he glimpsed collections of stars through

the tops of the trees. He hoped that Lorraine was safe and felt

uneasy about letting her go back to the B & B earlier that

evening. She had been tired after the trip up from New York

and after the dinner, when the conversation between their table-mates

faltered, she yawned. Raymond happened to be watching her at

this moment and the sight of his wife yawning terrified him.

After she took her hand away from covering her mouth, he noticed

how the lower lids of her eyes glistened with the tears welled

there. He could not tell her but he felt an inexplicable fear,

not a sense of foreboding but something deeper and less random.

He felt it was a moment that he could see her, a moment of clarity,

and in this moment she seemed completely inured of him. She

smiled and told him that she was going to take the car back

to the bed and breakfast and he, alarmed by the casual gesture

with which she declared boredom with her life, could not tell

her that he needed her to remain there.

He hoped he would feel better once she was gone but his discomfort

only worsened, the vodka having the opposite effect and heightening

his senses. The tent crackled with sound: words he could not

make out, voices billowing into white noise. He closed his eyes

but saw his wife with her hand to her mouth.

“You okay now Allen?”

“Sure. Yeah. Hey look, I’m sorry about everything.”

Now hitting a long stretch of straight road, Allen turned around.

His eyes were red-rimmed and the lower lids puffy; to Raymond

they looked like auxiliary mouths, little ones, each holding

a great gumball of an eye. Raymond shrugged and then lifted

his chin to indicate that he would appreciate Allen’s

full attention being focused on the asphalt ahead of them.

“Why are you so upset?” Raymond asked.

Allen looked at him through the rear-view mirror. “It’s

nothing.”

“I’m sorry. That was a personal question.”

Lorraine often chastised his tendency to ask questions of complete

strangers, which he took as a compliment. Once, after attending

the funeral for his wife’s aunt, Raymond left the crowd

milling around the doors of the memorial chapel and wandered

off to find two men digging a grave. He stopped and asked them

how long it took to dig a grave properly and if they really

had to go six feet down. At first the two men thought he was

a wise-ass or someone from a government agency, but they soon

realized that he was genuinely interested. One of them, a huge

black man with a right eye made milky by a cataract and who

introduced himself as Clyde, told Raymond there were strict

rules about depth, state regulations; and that while the job

was generally enjoyable, it was more difficult in the winter

when the earth cooled and became rock-hard. The other man, who

did not bother telling Raymond his name, bragged that he had

just helped exhume a body for the coroner’s department.

“It’s funny though,” Allen said, as though

he wanted to continue talking.

“What?”

“When I said. “It’s nothing’, it’s

sort of true,” Allen said, now staring ahead as they passed

a sign directing them to North Hyde Park. “I got a depression.

The doctor says it’s due to nothing in particular. He

said that depression is different now and it doesn’t have

to be because of something anymore.”

“Oh yeah, like brain chemicals and stuff.”

“Exactly. Hey, you depressed too?”

“No,” Raymond replied.

“I was waking up at four in the morning and I wasn’t

eating and I was anxious all the time,” Allen said, and

Raymond wondered what sort of low-balling HMO he had if he was

forced to continue driving private cars around and weeping at

the wheel. “It still gets to me, now and then. Less since

I’ve been on antidepressants.”

“Yeah, you better now?”

“I think so. It’s slow, though. I thought something

would be at the bottom of it, but there wasn’t anything

there.”

But Allen was right, he thought, it was odd, and frightening

in a way, that something as black and enveloping as depression

could just descend without a cause. He looked at Allen’s

head. Somewhere in Allen’s brain something had happened:

a memory, a chemical, a sadness blossomed. It would push him

to wake up early or stop talking or step off a bridge. It happens.

Raymond had, at one time or another, considered his mother to

be depressed; she was a woman given to periodic and lengthy

turns in bed followed by over-enthusiastic appearances at charity

functions, forever with a glass in her hand. His father, if

he was depressed, sought solace in the therapeutic effects of

battering his family with the volume of his voice, and serial

infidelity. Now they lived in Vermont and were happy. He could

not dispute it nor for a moment comprehend it.

Parts of the road now seemed familiar, a ridiculous notion to

Raymond as the darkness and the speed of the car made everything

fade and shift and nothing could be recognized. He longed to

be in a strange bed with his wife, with someone who inexplicably

loved him and whom he loved, someone who slept, waiting for

him. For a moment he felt as though he were above the trees

and the rural roads and in the air again, quiet under the stars,

engines shut off and simply drifting. He thought of Lorraine

lying in bed, of the body that shared space with his, and he

yawned. The road was familiar, he knew they were close. His

eyes followed the thickets along the side of the road—dark

and undulating, without break or variation—until suddenly,

two stunning green points of light appeared in the underbrush

and then a flash of white rose up and out of the darkness to

take the form of an animal rushing over the car and past his

head. He looked back but saw nothing.

|

|

|