THE ROAMERS

the art of

ROBERTO ROMEI ROTONDO

by

ROBERT J. LEWIS

_______________________________________________________________________________

When

painting ranks as the supreme value it has no concern

with, and no place in, a social order that, itself, lacks

any supreme value. André Malraux. The Voices

of Silence.

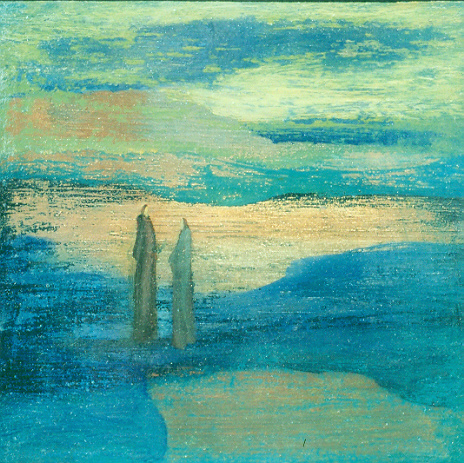

The series

entitled The Roamers, by Italian-born, Montreal-bred, Roberto

Romei Rotondo, is a remarkable achievement because

it challenges our preconceived notions of modern art while revitalizing

an art form that has long since fallen off the critic’s

radar screen. I’m persuaded that the series, completed in

2003, will emerge not only as the artist’s greatest work,

but will come to be viewed as a significant creation because there

is no where for that kind of 3C (color, canvas, and concept) painting

to go. As a modern art that does the past proud, The Roamers,

which exists separate from the ‘isms’ that legislate

rank and relevance, discloses a realm where figuration is subsumed

by abstraction, but never disappears in it. By dispensing with

the conventional foreground-background dynamic, The Roamers satisfies

the conditions of both figurative and abstract art and demonstrates

their easy co-existence. That there is nothing new in this is

to miss the point; the artist is neither an innovator nor obsessed

with notoriety. “I don’t require a hardware store

or plumber’s kit for the materials of my art,” he

declaims.

Rotondo

describes himself as an admirer of de Stael (1914-55) for whom

pure art is incompatible with any conceptual and/or didactic design,

the movement towards which culminates in the art of Rothko and

Newman. If Cezanne’s revolutionary art was motivated by

his fear of pictorial depth disappearing forever, Rotondo, perhaps

fearing for the life of ideas in painting, turns de Stael into

a radical point of departure and evolves, through the introduction

of deliberately open-ended, receding subject matter, a conceptual

art that is metaphysical in reach, where the meaning of a work,

or the series, runs parallel to the viewer’s interrogation

of his own life. At the same time, at the bidding of the viewer,

each work in the series can be appreciated for its decorative,

non-conceptual, surface properties. Through an unlikely marriage

of highly refined Renaissance brush work and Expressionism, the

artist’s layered approach to color and rigorous application

of abstract principles of composition combine to produce two new

aesthetics: of civility and silence, idioms which, prior to Rotondo,

were only partially disclosed, but following the precedent of

Mondrian, whose exemplary compositional formulations have not

been surpassed, adhere to the laws of balance that govern color,

tone/light and volume.

If it

is the unstated ambition of every painter to produce a body of

work that will not only satisfy the conditions of great art but

resonate for all times, he will do so by responding to the significant

concerns of his time in such a way that future generations viewing

his work, will be taught to respond to their own. The Roamers

is a candidate for such an art because -- pacing American literary

critic Robert Trilling -- it competes with the ideas of philosophy

and illuminates the realm of philosophical enquiry like no other

art in the history of contemporary art; and may prove equal to

the ideas of the great religious paintings and statuary that emerged

under Christianity.

We

first meet the prototype of The Roamers in a series of unpublished

notebook size monochromatic oil sketches on paper, (2001) called

The Caves, which foretell the color, contours, and conceptual

themes The Roamers will bring to completion 3 years later. In

many of these sketches the protagonists have not so much withdrawn

from the daily grind but have refashioned it to facilitate the

contemplative life. At first glance, we encounter, without fanfare,

unremarkable gatherings of people who are imprecisely engaged

with one another. In the tradition of Van Gogh’s feel for

architecture, (the Church at Auvers), a straight line is not to

be found, while the settings, albeit far removed from modernity,

are neither mythical nor idealized. But when we allow the eye

the time required to meet the work half way, we discover that

the first effect of the diaphanous quality of the sketches is

to mysteriously render unfamiliar that which we would normally

regard as understood, and that what animates these quaint gatherings

is not mere conversation (chatter) but dialogue of the highest

order, the recognition of which becomes both the delight and device

of The Roamers.

We

first meet the prototype of The Roamers in a series of unpublished

notebook size monochromatic oil sketches on paper, (2001) called

The Caves, which foretell the color, contours, and conceptual

themes The Roamers will bring to completion 3 years later. In

many of these sketches the protagonists have not so much withdrawn

from the daily grind but have refashioned it to facilitate the

contemplative life. At first glance, we encounter, without fanfare,

unremarkable gatherings of people who are imprecisely engaged

with one another. In the tradition of Van Gogh’s feel for

architecture, (the Church at Auvers), a straight line is not to

be found, while the settings, albeit far removed from modernity,

are neither mythical nor idealized. But when we allow the eye

the time required to meet the work half way, we discover that

the first effect of the diaphanous quality of the sketches is

to mysteriously render unfamiliar that which we would normally

regard as understood, and that what animates these quaint gatherings

is not mere conversation (chatter) but dialogue of the highest

order, the recognition of which becomes both the delight and device

of The Roamers.

Before

Rotondo turned to painting, he was immersed in the study of philosophy:

Heidegger, Nietzche and the Pre-Socratics. Well before bin Laden

turned the cave into a sound-byte zone, and well after man’s

first essays at primitive art in the caves of Lescaux, Plato’s

cave allegory was the most discussed cave in history and was the

site where philosophical discourse was formalized as a dialectic.

Which is to say, Rotondo’s choice of the cave and variations

as the setting for his sketches and later work is hardly an accident.

The

seductive qualities of The Roamers cannot be separated from their

philosophical underpinnings. If his work -- most of which features

informal gatherings of people -- doesn’t reveal its meaning

at first glance, the idea of the philosopher kings prevails throughout,

and like a friendly breeze imbues his work with a lyricism that

is tantamount to the artist’s signature.

The

seductive qualities of The Roamers cannot be separated from their

philosophical underpinnings. If his work -- most of which features

informal gatherings of people -- doesn’t reveal its meaning

at first glance, the idea of the philosopher kings prevails throughout,

and like a friendly breeze imbues his work with a lyricism that

is tantamount to the artist’s signature. Set against the tempest winds of modernity that provide one rush

after another but no meaningful direction, The Roamers introduces

the notion that there exists a significant connection between

authenticity and serenity, the deficit and syntax to be supplied

by the viewer. Which leads us to the maker’s uncompromising

pallet where paint and meaning are masterfully mixed and singularized,

a feat that speaks to an artist in complete control of his art

and vision, for whom painting is the site where he reveals his

care and concern for the destiny of the world. Unlike abstract

artists, Rotondo refuses to leave the content of art to the caprice

of the beholder, and he categorically rejects the view that art

no longer require a consensus to be significant art. The Roamers

is first and foremost a conceptual art whose agenda is formalized

through its painterly qualities and compositional rigor, where

volume and content are arranged to throw, not into sharp, but

gradual relief the idea that in our rush to modernity we have

lost something vital, an essential part of ourselves; and as the

viewer struggles to uncover the implications, he is introduced

to his own spiritual indices.

Set against the tempest winds of modernity that provide one rush

after another but no meaningful direction, The Roamers introduces

the notion that there exists a significant connection between

authenticity and serenity, the deficit and syntax to be supplied

by the viewer. Which leads us to the maker’s uncompromising

pallet where paint and meaning are masterfully mixed and singularized,

a feat that speaks to an artist in complete control of his art

and vision, for whom painting is the site where he reveals his

care and concern for the destiny of the world. Unlike abstract

artists, Rotondo refuses to leave the content of art to the caprice

of the beholder, and he categorically rejects the view that art

no longer require a consensus to be significant art. The Roamers

is first and foremost a conceptual art whose agenda is formalized

through its painterly qualities and compositional rigor, where

volume and content are arranged to throw, not into sharp, but

gradual relief the idea that in our rush to modernity we have

lost something vital, an essential part of ourselves; and as the

viewer struggles to uncover the implications, he is introduced

to his own spiritual indices.

Rotondo’s

narratives unfold in earthy-warm, primitive settings, where elongated,

heaven-wreathed, wraithlike characters gather and engage in civilized,

elevated discourse, to the effect that without knowing why, we

want to be there with them, in their most intimate community,

as if being-there would fill a void his art insists we take notice

of. The relative smallness of his characters set against the immensity

of nature is not a contrived humility, but a proportionate response

to the human condition marked by suffering and loss, events to

which the tormented creator of The Roamers is no stranger.

Rotondo’s

narratives unfold in earthy-warm, primitive settings, where elongated,

heaven-wreathed, wraithlike characters gather and engage in civilized,

elevated discourse, to the effect that without knowing why, we

want to be there with them, in their most intimate community,

as if being-there would fill a void his art insists we take notice

of. The relative smallness of his characters set against the immensity

of nature is not a contrived humility, but a proportionate response

to the human condition marked by suffering and loss, events to

which the tormented creator of The Roamers is no stranger.

Despite

the cynicism that characterizes modern art in both its content

and execution, The Roamers is an optimistic work, and is the answer

to Munch (Scream) and especially the art that culminates in minimalism.

The artist has laid bare a vision of man, very much of the earth,

of the soil, that invites us to undertake a journey -- the title

of an earlier series -- the purpose of which is what we make of

it, even though it is impossible not to notice that in many of

The Roamers the characters are illuminated by the Christian halo

and its pre-ordained significations. My first thought was do we

have to be told that the artist’s work is underwritten by

his genuine spiritual concerns? After all, aren’t his sublime

personages already somewhere between man and God, already dwelling

in the exalted terracotta of an alternative world? If it is no

secret that the painter is a devoted  Catholic,

whose life has been informed by the Bible (especially those injunctions

that encourage the partaking of wine), it should be said that

I’m a secularist, drawn toward the all-inclusive, non-denominational

temperament of his work. Which means, as a responsible critic,

it is my duty to declare my own biases and refrain from imposing

them on a body of art whose intentional thrust clashes with my

own. If I disingenuously insinuate my world view onto The Roamers,

I become party to a position that betrays their spirit: a witting

cheerleader or acolyte of modernity for whom secularism is merely

another alibi for another kind of intolerance. For the record,

and for the millions of traditionalists world-wide and the churches

that attend to their spiritual needs, Rotondo’s halo-charged

work will surely find a home, just as the form and hues of his

halos are integral to both the concept and composition of his

work.

Catholic,

whose life has been informed by the Bible (especially those injunctions

that encourage the partaking of wine), it should be said that

I’m a secularist, drawn toward the all-inclusive, non-denominational

temperament of his work. Which means, as a responsible critic,

it is my duty to declare my own biases and refrain from imposing

them on a body of art whose intentional thrust clashes with my

own. If I disingenuously insinuate my world view onto The Roamers,

I become party to a position that betrays their spirit: a witting

cheerleader or acolyte of modernity for whom secularism is merely

another alibi for another kind of intolerance. For the record,

and for the millions of traditionalists world-wide and the churches

that attend to their spiritual needs, Rotondo’s halo-charged

work will surely find a home, just as the form and hues of his

halos are integral to both the concept and composition of his

work.

If

what finally distinguishes significant art is its ability to turn

the viewer into an accomplice, Rotondo’s The Roamers answers

every challenge and already stands as a formidable rampart against

what has yet to be properly identified as the crisis in modern

art. Whether or not the next cycle of painting rises to the occasion

of offering a correction to the art -- or what has been passed

off as art -- of the past 50 years, just might depend on the reception

of and precedent set by The Roamers, and in general, the artist

taking responsibility for the unceasing line that charts the ups

and downs, the rises and crises in the history of art.

If

what finally distinguishes significant art is its ability to turn

the viewer into an accomplice, Rotondo’s The Roamers answers

every challenge and already stands as a formidable rampart against

what has yet to be properly identified as the crisis in modern

art. Whether or not the next cycle of painting rises to the occasion

of offering a correction to the art -- or what has been passed

off as art -- of the past 50 years, just might depend on the reception

of and precedent set by The Roamers, and in general, the artist

taking responsibility for the unceasing line that charts the ups

and downs, the rises and crises in the history of art.

All works ©

Roberto Romei Rotondo