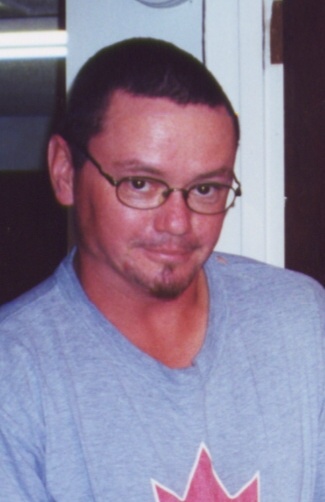

Sean

Johnston is a Saskatchewan writer who works as a surveyor in BC.

The Underdog is from A Day Does Not Go By (Nightwood 2002).

The manuscript for the collection won the 2002 David Adams Richards

Prize.

Sean

Johnston is a Saskatchewan writer who works as a surveyor in BC.

The Underdog is from A Day Does Not Go By (Nightwood 2002).

The manuscript for the collection won the 2002 David Adams Richards

Prize.

*

* * * * * * * * *

The underdog was drawing water,

with that horrible clanging and creaking machine. He was at that

terrible well, and paused to put his hair behind his ears. The

bucket was too big for him. It was too big for all of us, but

he insisted on going. We needed water.

"I'll be careful,"

he said all the time.

There were snipers all around,

in those days. We can't explain it now, but we took it for granted

then. He was at that well, and we waited for the crack of a gunshot.

"I'll be careful,"

he had said. Sure enough, he was.

It's a different kind of care,

he would say. Degrees and so on. The care in tying a shoelace,

not the care in avoiding moving wheels. The care in not breathing

second-hand smoke or wearing very tight briefs, not the care of

stooping just under the bullet.

His face was red with exertion

and we waited for the air to change sounds-a gunshot, a stop to

his labored breathing. When it did, we imagined the worst, naturally.

But it was only the platform had broken. He was all right but

for the broken ankle.

A doctor was sent for. He smiled

and sweated. We boiled our tea. We understood.

The ground is soft and wet this

morning. The movies play on. This air is fresh!

We watch the underdog. What will

he do now? And we cheer for him silently. He doesn't know he's

the underdog.

The preacher's wife was disappointed.

"It's a pity we loved him,"

she said.

Her hair was trim and dark. Her

narrow hips confined her movements to thin arcs, and the gestures

of her lips showed us no one knew better. When she continued speaking,

and anger sparked in her eyes, the preacher broke out of his meditation,

moved to see her as human.

"We have all been misled,"

he agreed. "Now let's begin the next part. Let's begin to

learn what this man is, if he is not an underdog."

In the antique room, with its

stale walls beaten and full of holes, the air was fresh. It came

from outdoors. The underdog sipped tea with us, keeping his ankle

carefully elevated, propped on a pile of rubble. The rubble was

on a warm wood hope chest that had been disfigured by fire.

I looked at the preacher and

his wife. He was taking it better than she was. The doctor was

embarrassed. The gunfire had gone somewhere else, but the signs

of the war did not let us believe it was gone forever.

You all think of your roles,

I thought, and look at the underdog smile. Look at how tired he

is. Look at his missing ear. See his bent ankle and its makeshift

cast, a tight bandage made stiff by dirt. How has his injury made

him less an underdog?

When he fell asleep, or when

we heard him snore to prove he was asleep, the doctor could honestly

address us all:

"Look, I am a doctor,"

he said. "My job is to make people better. My job is to heal

people if I can. I'm sorry."

None of the cowards would admit

they cared. I also said nothing.

The war is ending and there are

trains to catch. A small woman from the city, Lara, speaks to

him on the platform. We wince as we see them both smile.

She holds her tiny purse with

both hands in front of her, and looks down at her feet. He blushes

when she looks up again, catching him in full rapturous stare

at a ringlet that falls from her tight pink hat just in front

of her ear. She kisses him on the cheek and whispers her phone

number. Specific to the period, nice girls don't do that.

She comes from a nice family

and she's going nowhere, but enjoys herself. She does nothing

wrong, exactly. But when she does right, it's not necessarily

on purpose. Is it wrong?

I said it in a bar once and it

didn't go over very well, except with the preacher's wife.

"Sometimes I would like

it all to be done with," I said.

Because some of it, honestly,

is pure cruelty. There are times when I want it to be over. I

want him to be just a figure. Just an idea.

The preacher raised his head

and said we all do, then lowered his eyes to the table again.

His wife had asked for the car keys hours ago.

"I mean I want sometimes

to do it myself," I said. "I want to knock him down.

I want to see the stunned look on his face!"

I slammed my glass on the table

and pulled a cigarette from the pocket of the preacher's wife's

coat.

"It's like rubbing a sore,"

I explained. "Sometimes I can't look at him but I do."

The preacher had his eyes shut

and was smiling. His wife took my hand.

"Then next time you see

him and he's happy or sleeping-" she said.

"You can't help it! You

want him beaten and tired!"

We weren't that drunk, the preacher's

wife and me. The preacher opened his eyes. He took his wife's

other hand. He couldn't believe what he was hearing.

"He's a fine man,"

he said, mostly to himself. "You want to hurt him?"

Our waitress came by and we sobered

up with coffee. The underdog came in, in one of his good moods.

I smiled and said hello.

The preacher had enough shame

for all of us.

The preacher's wife had her tongue

in his ear and I don't think he noticed.

"Off to the movies with

Lara!" the underdog said with a wink. His poor red face wanted

his body to run, but he walked to the door without skipping.

"She's beautiful,"

we said, but he was already gone and he already knew.

Free, after the war, a survived

underdog, the ultimate hero, he went about it all wrong. He did

what he could. He muddled through. He eked out a living.

Lara was gone. We knew she would

be. She had found a man who, if he had ever been less than a hero,

hid it extremely well. They loved each other and who's to say?

Things are right for a reason. The green lawn and the sunshine

is what we all want. The preacher's wife should never have married

him. She wanted a man who would die, she wanted Jesus Christ,

she wanted to be a widow, and who can say she was wrong? She cut

quite a figure. She worked her way into all of our hearts. The

preacher's too-but she would not let him be human, except in his

suffering.

The underdog had a crisis of

faith years after the war.

"Everyone I know measures

themselves against their reaction to me," he said.

"Your excuses for the unfinished

house are wearing thin," his wife said, applying a lint brush

to the suit on his back. She held the brush up to the window and

looked at it in disgust.

"The children cannot see

me as their father -"

"Of course you're their

father," she said. "I can't believe the way some people

-"

"They can't see me as their

father," he said, shaking his head.

He turned to face her and she

watched him silently, the lint brush still in her hand. He walked

over to the sink, taking his jacket off and hanging it on a kitchen

chair. He turned the tap on and ran himself a glass of water.

He held it to the light from the window and waited until the sediment

settled and he could see through it clearly. She sat down in the

chair his jacket was on and watched his back. A sweat stain was

beginning between his shoulder blades.

He drank the water and turned

to her.

"My own children pity me,"

he said.

She shook her head as she rose

and walked toward him.

"That was good," he

said, and ran more water. "Cold."

She put her arms around him and

leaned on his back, clasping her hands around his waist and pulling

herself more tightly toward him.

"I loved another woman once,"

he said.

"I know. Her name was Lara.

I knew her. We were friends."

"We all were," he said,

setting his glass on the counter and turning to face his wife.

His red face trembled. "I have failed at everything I ever

tried. My boy pities me and my daughter will as soon as she's

old enough."

"They envy you," she

said. "Everyone does. Your boy wants to kill you sometimes.

That's just how boys are. Your daughter thinks you made this world

and everything in it."

"We are all exceptions,"

he said, hugging her tightly. "But sometimes I feel like

. . . "

Tears rolled from his eyes down

his sore face. She kissed him on the cheek.

. . . an archetype, he thought.

The underdog was tying ribbons

around some neighborhood trees the last time I saw him. I was

on my way to Kinko's for some copies.

"Hi there," he said.

I walked over to the graying

man squinting in the sunshine. He needed a rest.

"Good to see you,"

I said. "What is all this for?"

"Lara's son is one of the

hostages," he said, nodding sadly. Then he gave me a hug.

We're all still here. We all

still live in this town. He and his wife have a new child. Nobody

thought it would happen. There is a home on the outside of town

full of people the doctor has saved. The preacher went back to

school to be secularized. His wife was secularized as a baby.

I'm plastering the town with posters, asking everyone to reconsider.