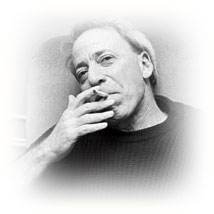

David

Solway is the author of many books of poetry including the award-winning

Modern Marriage; Bedrock; Chess Pieces; Saracen Island: The

Poetry of Andreas Karavis and The Lover's Progress: Poems

after William Hogarth, the latter illustrated by Marion Wagschal

and adapted for the stage by Curtain Razors. He has recently completed

a new collection of poems entitled Franklin's Passage,

forthcoming with McGill-Queen's University Press in Fall 2003,

and is now working on his fourth book in education and culture,

entitled Reading, Riting and Rhythmitic. A collection of

literary/critical essays, Director's Cut, is due out with

The Porcupine's Quill in Fall 2003 and a novel, The Book of

Angels, is slated for Spring 2004 with Mosaic Press. He is

currently a contributing editor with Canadian Notes & Queries

and an associate editor with Books in Canada.

David

Solway is the author of many books of poetry including the award-winning

Modern Marriage; Bedrock; Chess Pieces; Saracen Island: The

Poetry of Andreas Karavis and The Lover's Progress: Poems

after William Hogarth, the latter illustrated by Marion Wagschal

and adapted for the stage by Curtain Razors. He has recently completed

a new collection of poems entitled Franklin's Passage,

forthcoming with McGill-Queen's University Press in Fall 2003,

and is now working on his fourth book in education and culture,

entitled Reading, Riting and Rhythmitic. A collection of

literary/critical essays, Director's Cut, is due out with

The Porcupine's Quill in Fall 2003 and a novel, The Book of

Angels, is slated for Spring 2004 with Mosaic Press. He is

currently a contributing editor with Canadian Notes & Queries

and an associate editor with Books in Canada.

* * * * * * * * * *

| |

One may review an actual situation by redescribing it

without making any mathematical or logical statement.

John Wisdom, Paradox and Discovery

|

|

| |

| |

I cannot put the subject through his paces in my inquiries

into his inclinations as I can in my inquiries into his competences.

Gilbert Ryle, The Concept of Mind

|

|

As a student at the university

I intended to become a professional philosopher. I took my quota

of graduate courses, learned to smoke a fisherman's pipe, and

celebrated Kant's birthday by drinking his favorite wine and speculating

on the Transcendental Unity of Apperception. The pipe in particular

was indelibly associated with the pursuit of wisdom. The cigarette

belongs to the poet with his nervous, sporadic inspirations and

the cigar to the novelist, the verbal tycoon, with his larger

and more relaxed rhythms of composition. But the pipe is the philosopher's

congenial instrument. The amount of time and fussing it requires

to be kept lit furnishes the thinker with massive intervals of

unrelated activity in which to formulate his abstruse and ineffable

ideas. This was especially true of Kantian studies where what

might be benignly construed as a scholarly accessory assumed the

status of a rigorous prerequisite. Our sessions over the Critique

of Pure Reason, however, in which we tried to emulate our

professor's sobranie meditations, had the opposite effect on us.

Smoke billowing from our intellectual chimneys, we coughed a lot

and our eyes watered copiously in an enveloping atmosphere of

fug and dottle. But we puffed heroically away as we gradually

lost touch with the Paralogisms and saw the Axioms of Intuition

recede into the double obscurity of philosophical jargon and visual

occlusion. We had obviously a long way to go to master the art

of Transcendental scrutiny.

I attended courses in Ethics

in which we were taught to discriminate between the cash-value

of practical conduct and the rubber cheque of utopian imperatives.

I was deeply impressed by my teacher in Greek philosophy, the

kindly and diffident scion of a wealthy family, who had met Bertrand

Russell-"good old Berty" as he called him-in his Yale

days, discoursed endlessly on the Parmenidean dictum that Whatever

Is, Is, and was chauffeured to class imposingly ensconced

in the back seat of a big, green Bentley, like Plato sailing plutocratically

into the court of Dionysus of Syracuse. And I was duly terrified

by a lean, dry, inexorable Englishman who operated linguistically

on such innocent statements as "Bismarck was an astute politician,"

disdained a priori concepts, and befuddled us with assertive links,

ifs and cans, and illocutionary sentences.

Because the department was of

the Analytic persuasion, it compensated for its bias with the

occasional expensive French import. This was how the famous commentator

on Sartre, Jean Wahl, found himself scurrying frantically between

library and office, classroom and coffeehouse, always on the go,

as if to present a moving target or stay out of the firing range

of what must have appeared to him as a cavalry of jodhpured Positivists.

As he was scarcely five feet high, the joke made the rounds that

Jean Wahl had committed suicide by jumping off a curb.

The conflict that divided us

in those days and set philosopher against philosopher in crusades

of internecine pettiness was that between the British and Continental

schools, a hangover from the English blockade of Napoleon. Empiricists

and Existentialists could not bear to be in the same faculty lounge

together. There was an apocryphal story that dramatized the absurdity

of the dispute. At a prestigious conference of contemporary philosophy,

a British Empiricist condemned the Continentals for vagueness

of phrasing and hyperbolic imprecision of thought. "Tell

him," said a leading French Existentialist on hearing of

this piece of defamation, "that he is a cow."

The reason I did not take sides

was that they were all equally bewildering: Kantians, Neo-Thomists,

Positivists, Hegelians, Phenomenologists, Ordinary Language philosophers,

the whole sick crew, as Thomas Pynchon would say. To use the choice

word of Humpty Dumpty, the teetering founder of the school of

Linguistic Analysis, they were of an unbreachable "impenetrability"-which

meant, according to this learned arbiter, "We've had enough

of that subject, and it would be just as well if you'd mention

what you mean to do next, as I suppose you don't mean to stop

here the rest of your life." Nevertheless, I persisted, deaf

to good advice. Wittgenstein's Tractatus left me cold.

I could not get past his paragraph numerology and agreed only

with his conclusion, "What we cannot speak about we must

pass over in silence," because that at least was understandable

and because it coincided with Hamlet's dying speech. As for Husserl's

Ideas, not a single word registered, and his Cartesian

Meditations drove me to paroxysms of incomprehension. Switching

to Willard Quine was no antidote: identity, ostension and hypostasis

made one feel as if one were developing cataracts. Heidegger was

a disaster and I could see him only as the reverse counterpart

of his namesake in Nathaniel Hawthorne's short story Dr. Heidegger's

Experiment: Hawthorne's doctor possessed an elixir that

made people younger but the torpid prose and tortuous thinking

of the German philosopher aged me overnight. Clarence Lewis was

better. The only problem with Mind and the World-Order

was trying to divine why it had been written in the first place,

as it seemed no more than the unfolding of a colossal tautology.

Who had ever doubted that experience was such as to be amenable

to conceptual formulation?

At one point I decided the only

solution was to apply to the oracle himself. Accordingly, I sent

off a letter to "Berty" who was living in Wales at the

time, offering my services as amanuensis, occasional chess player

and loyal apprentice. I described the turmoil and confusion generated

by my studies and even confessed to a certain boredom. Praising

the titan for his indefatigable brainwork, his espousal of noble

causes and his legendary excesses in the matrimonial field, I

promised to be a good companion, a devoted student, and to let

him win from time to time at chess. The letter concluded by congratulating

the old man on his longevity but reminding him that even genius

as it ages requires infusions of new blood, fresh perspectives

and the intellectual buoyancy only youth can provide. The aging

genius did not reply, an omission which looked at first like a

personal insult and only afterwards as a critical appraisal of

my philosophical ambitions.

As the semesters went by my faith

began to waver. I was the only one in the class who thought that

Samuel Johnson's refutation of Bishop Berkeley's principle of

Subjective Idealism, namely, esse est percipi or to be

is to be perceived, was basically sound. The perambulating doctor

had kicked a curbstone and uttered the immortal words, "Thus

I refute Bishop Berkeley." To defend this position was like

siding with Cardinal Bellarmine. The seminar room presented another

major problem. It had no windows. At the end of a three hour class

on the Categories or the Dialectic the hallucinations came thick

and fast and I would dash madly down the stairs, too desperate

to wait for the elevator, just to reassure myself of the continued

material existence of the ginko tree at the top of the campus.

It was growing increasingly clear that although my grades were

reasonably good my prospects were not and that a philosophical

career might be nothing more than a pipedream.

One evening I visited the most

brilliant student in the department who had devised a kind of

Mercator projection of Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit.

It was a road map of the Absolute, about one meter square, which

resembled a cross between a genealogy table and the Tibetan

Book of the Dead. Everything was neatly marked in black ink.

All of Hegel, the whole labyrinthine country of that cluttered

and tenebrous mind, lay spread out before me, while my benefactor

performed miracles of explanatory acrobatics. When I left, I was

more in the dark than ever.

The time had arrived to submit

my thesis proposal to the department moguls. I had decided that

what was missing in philosophy, as currently practiced and taught,

was the sense of wonder and delight which had presumably informed

its beginnings. Thus I proposed a return to origins to which,

as a student under the age of twenty, I was manifestly closer

than my teachers, who were all over forty. Basing my intentions

on the models of Parmenides and Lucretius who wrote in verse,

I notified my advisors that I was ready to tackle the enigma of

existence in all its primeval and crepuscular splendor and, moreover,

would do so in decasyllabic metrics. Instead of a prefatory Abstract,

there would be an epigraph, suitably ambiguous, taken from Milton's

Il Penseroso: "Where glowing embers through the room/Teach

light to counterfeit a gloom." The stares of incredulity

and affront which greeted this proposal served merely as a mild

prelude to the storm of abuse that broke over my poor, unmortarboarded,

anti-philosophical noggin. My betters were both stupefied and

amazed. Philosophy, it seemed, not only began but ended in wonder.

In the name of Wisdom, the presiding rota was incontinently Ryled.

Poetry, it must be remembered, operated as a rhetorical dismissive-"That's

just poetry," the profs would sneer when crushing some notion

or proposition advanced by their romantic catechumens. To address

oneself not to the tidily articulated commonplaces of a celebrated

British Analyst, preferably P.E. Strawson or A.J. Ayer, but to

the richly inscrutable cosmic text authored by a nonentity and

philosophical tyro like God, and to suggest verse as an appropriate

medium for cognitive inquiry rather than the narrow and exclusionary

technolect favored by a club of fastidious empiricists, was about

as close as one could get to the kiss of academic death.

I was slowly coming to see that

my philosophical career was in considerable jeopardy. Part of

the trouble was that I had no Socratic daimonion, no inner

voice that could always be counted on to tell one what not to

do. If anything, I was possessed by its polar opposite, a perverse

little devil out of Edgar Allen Poe with a nasal twang egging

me on to behave in ways precisely calculated to erect obstacles

in my path, like proposing a thesis in verse on the prepreSocratics.

Nevertheless, the temptation of secret gnosis continued irresistible.

I loved the gnarled and idiosyncratic rhetoric of the German metaphysicians

as I admired the ostensibly crisp and limpid prose of the 18th

century Brits. The fact that I understood little of what they

wrote did not deter me from seeking the invisible grail of wisdom

that surely lay at the core of their testimony. And there was

always the hope that one day I might experience the moment of

visionary consummation, the noematic indescribable, the Kantian

ding an sich, the Platonic eidos, the Aquinian music,

in short, paydirt. My little impish voice said, "Go for it."

And, credulous as always, I went for it, enduring yet another

year of the Higher Bafflement.

Nothing offered to lighten my

miseries, not even the occasional social encounter. I had made

friends with a graduate student who intended to become a Neo-Kantian

and we would regularly engage in long, pointless controversies

over esoteric and insignificant questions, such as whether one

could really generalize the maxim of one's conduct and whether

one should do away with oneself if one couldn't. Debating such

deep and pressing issues, we found ourselves one evening at a

Graduate Society party, smoking our pipes, wearing the obligatory

tweed with leather elbows to complement the solemn expressions

we assiduously cultivated, pretending to be oblivious to the fact

that all the girls we secretly coveted seemed sublimely unaware

of the charms of philosophical discourse and plainly preferred

the company of sweet-talking literature majors and budding biochemists.

Even the psychology and economics students were doing alright

compared to us. It came to me in a flash that "doing philosophy,"

as it was then called, was tantamount to committing eroticide,

and that it didn't matter one bit if one could generalize the

maxim of one's conduct or not because, whatever conclusion we

arrived at, whatever triumph of intellectual insight graced our

speculations, there could be no consolation for enforced celibacy.

"The parchment philosopher has no traffic with the night,"

as Elizabeth Smart told us. One might as well take Holy Orders.

The doubter was ripe for reality.

Now I had read my philosophers

at least well enough to know that reality was a problematic concept,

but this no longer appeared to matter very much. Whether reality

could be proven by kicking a curbstone-the same curbstone, probably,

that Jean Wahl jumped off-or by doubting everything but the cogito

that does the doubting or by bracketing empirical phenomena or

by relying on episteme rather than dianoia to furnish

a link with Truth or by catching a glimpse of the supersensual

Forms and the primum mobile or by hitching a ride with

World-Historical Reason on its way to Berlin, there was no point

going it alone. Condemning oneself to an existence without women

was nothing short of suffering a terminal deprivation of the Real.

But even though I was by this time convinced that a man's true

quest involved penetrating to the essence of muliebrity, aspiring

to that condition which Ezra Pound in an early poem described

as "after years of continence he hurled himself into a sea

of six women," I had not yet succeeded in shrugging off a

residual sense of guilt. Perhaps philosophy, like theology, subjected

its candidates to harsh preliminary deficits in order to reward

them at the end with the cash-value of knowledge and joy. Maybe

the girls came later. Or failing that, a vision of ultimate clarity.

Perhaps my thinking was still far too muddled to act upon. Should

I wait just a little while longer before embarking on new ventures?

Would lucidity finally arrive?

The coup de grâce

was administered by two French professors on loan from the Université

de Montréal who, riding in tandem, delivered a course on

Existentialism and Phenomenology as part of the department's affectation

of openness. To listen to the dual explication of Husserl in broken

English and in process of constant mutual interruption was like

falling under the simultaneous influence of alcohol and hashish-too

drunk to see one's deliriums clearly. I retired early and did

not attend another class for the rest of the term. Learning that

the final essay was due, I spent a weekend filling two examination

booklets with my cogitations on Gadamer and Dilthey, neither of

whom I had ever read, in a turgid and sibylline language borrowed

from Kant's Prolegomena. I was counting on the fact that

the professors were as foreign to English as their student was

to philosophy, but I did not expect more than a soupçon

of Gallic amusement. Quel divertissement! I received the

second highest grade in the course. At that moment, in a blaze

of sudden enlightenment, I understood the truth about reality:

reality was a dividend of not being found out, a credible simulation

of what did not exist, a function of A.N. Prior's logical operator

"Tonk"-the fudge factor that allowed whatever theory

of the world you were brokering to work, a kind of "runabout

inference ticket." In a word, reality was the genuinely inauthentic.

And since as a pseudo-philosopher I was already there, what would

be the point in prolonging the redundant? So it was I abandoned

the pursuit of the higher wisdom, free at last to indulge my natural

laziness and duplicity in good conscience and become a poet. And,

as always, richer in memories than in knowledge.